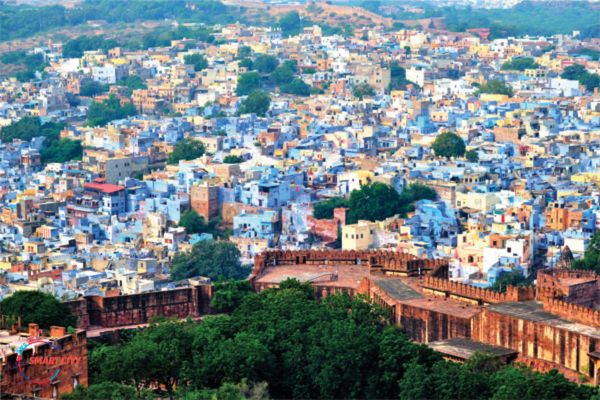

The simplest definition of collective identity is “the shared sense of belonging to a group.” It is also referred to as a socially influenced identity. Its relationship with architecture is two-way. Architecture is both a product of collective identity and a generator of collective identity. The blue settlement of Brahmapuri in Jodhpur represents a common set of values that bind the collective identity. The visual skyline of this low-rise blue section of the city is memorable for visitors and gives the city its identity as ‘the blue city of India.’ Landmarks such as the India Gate, the Red Fort, and the Taj Mahal serve as visual icons that we readily draw upon when trying to represent the nation. Hence, the nation is identified through iconic architecture from the past, among other means of defining it.

These simplistic examples highlight some concerns regarding the relationship between architecture and collective identity. The first concern is the emphasis on “visual” representations when associating architecture with identity. The use of visuals sometimes reduces architecture to identifiable symbols or certain typical angles from which it is photographed. By reducing an iconic built form to a symbol, its physical context may be fully eliminated from the visualisation, thereby separating it from its physical context.

Depicting skylines as identifiable cities is another reductive process that focuses solely on the visual dimension. This simplified visualisation process is often seen in drawings and paintings produced by young children when asked to represent a country or city. It stems from a conditioning that favours subject matter that is easy to simplify while eliminating what is complex, layered, and messy. It is a result of a purely objective approach in the teaching-learning process prevalent in mainstream education. This approach connects with collective identities on one end but also alienates individuals from articulating authentic lived experiences.

The built environment and its ‘image’ were highlighted as significant by Kevin Lynch (1960). However, he posited that environmental images are the result of a two-way process between the observer and the observed. While each individual may generate their own image, there are ‘public images’ or common mental pictures carried by a large number of a city’s inhabitants, based on their interactions and memories. Hence, the ‘image’ can be the result of an experiential process rather than purely a visual process. This points towards an approach that goes beyond the oversimplification of architecture to visual symbols in the generation of a collective identity.

Another aspect is how architecture from the past is judged in the present, based on politically charged notions of collective identity. The conscious production of certain collective identities is manifested in decisions regarding which part of the architecture from the past is to be glorified and which part is to be neglected or rejected. Hence, the ideas that bind the collective affect the future of architecture from the past, based on their associated meanings.

Also Read | A Water Policy for Urban Areas

The dominance of one collective identity over another has continued to play out over time, impacting the perception and physical condition of architecture from the past. This process continues in decision-making with respect to the production of built forms in the present day.

A compilation of inquiries into ‘Architecture and Collective Identity in the Contemporary City’ (ARGUS Night of Philosophy 2017) positions the notion of collective identity as challenging and challengeable. Identity is no longer a fixed condition but a ‘continually renegotiable site of individual expression’. In the 21st century, which is witnessing the disappearance of boundaries as the world gets connected through advances in communication technology, the idea of ‘collective’ is no longer solely based on geographical proximity. Cities have become more and more multicultural. Hence, the ideas of tradition and identity are shifting, and local identities are harder to define. This poses a challenging question for architects in terms of how the built environment should respond to these dynamic phenomena. The universalising tendencies of contemporary architecture, which make it ungrounded, do not help the cause either.

Views expressed by Dr. Parul Munjal, Director, INTACH Heritage Academy, INTACH